The Secrets of Seashells

The Secrets in Seashells – Video (All Ages)

Did you know that seashells not only look beautiful, but they also tell us about the environment in the ocean when the shell formed? Professor Maggie Cusack & Dr Javier Medina-Sanchez explore how scientists can use seashells like thermometers to find out the temperature of the seawater when the shell formed.

This video will also help be helpful revision on isotopes for anyone studying chemistry. Produced by the University of Stirling.

Shells on Acid! – Videos (10+) and instructions.

What’s the link between climate change and corals, mussels and oysters? Watch as Dr Susan Fitzer of the University of Stirling’s Institute of Aquaculture and Professor Maggie Cusack share their research, understanding how increased carbon dioxide levels affect an animal’s ability to grow its protective shell. With three experiments for you to try at home!

Ocean acidification is a future concern for animals that produce calcium carbonate shells such as corals, mussels and oysters. Shellfish grow protective shell structures through a process called biomineralisation. As increasing carbon dioxide in the atmosphere is absorbed into the seawater chemical reactions lower the pH making the seawater more acidic. Less carbonate is available for shell growth. Acidification also occurs at the coast where extreme rainfall produces excess carbon and sulphate soils make the water more acidic. Shells are made of different forms of calcium carbonate and some animals are more vulnerable to shell damage than others.

Shells on acid home experiments!

You can follow the instructions below or download the accessible PDF here

You will need:

Experiment 1. Natural acids and alkalines

Home experiment #1:

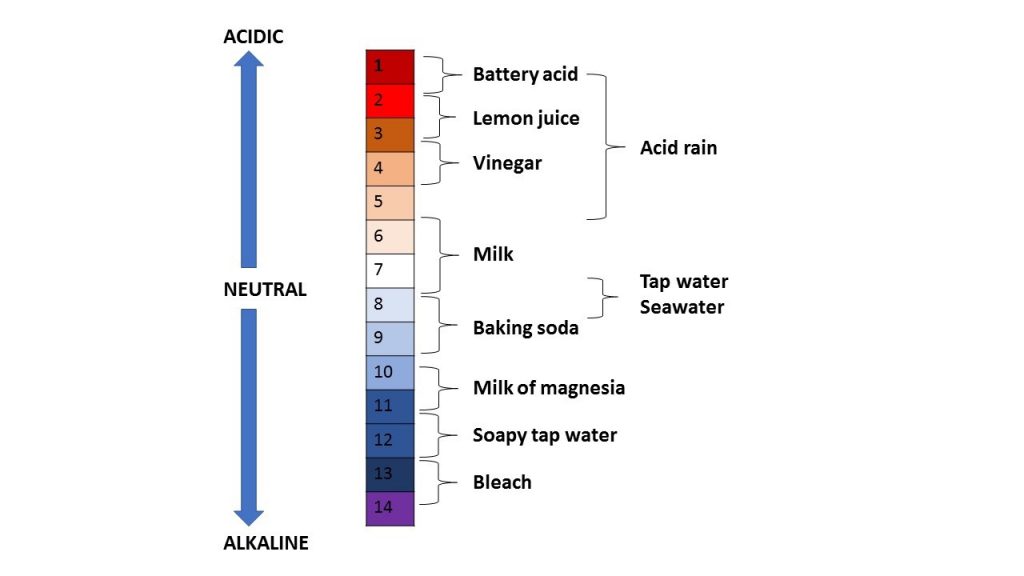

More info: The pH scale is a measure of the acidity of a solution and runs from 1 to 14. An acid is formed where hydrogen ions are dissolved into a solution reducing the pH. An alkaline is formed when a solution reduces its hydrogen ions increasing the pH. The pH scale is calculated on powers of 10 of the concentration of hydrogen ions in a solution. pH 1 is the most acidic, for example battery acid, and pH 14 is the most alkaline, for example bleach, as seen in the pH scale picture below. pH 1 is 10 times more acidic than pH 2. The image below shows the pH scale with examples of common acids and alkalines.

The pH of seawater is naturally alkaline at pH 8.0. As carbon dioxide is absorbed into seawater, chemical reactions occur reducing the pH making it slightly more acidic. This process is called ‘ocean acidification’.

Experiment 2. Shells on acid!

Home experiment #2:

See video instructions and explanation of the experiment here.

More info: Animals such as mussels, oysters and corals all grow calcium carbonate shells through a process called biomineralisation. Seashells are often in two main forms of calcium carbonate, aragonite, which is commonly called mother of pearl, and calcite. Mussel shells comprise of both aragonite on the inside of the shell and calcite on the outside of the shell. The aragonite is white and the calcite makes the blue part of the shell for common blue mussels.

In the above images, the blue calcite on the outside of the mussel shell (left) and white aragonite on the inside (middle image) of the mussel shell can be seen. The calcite and aragonite crystals can also be seen in the electron microscope image (right). The electron microscope image shows a cross section through a mussel shell from the outer calcite on the top to the inner aragonite on the bottom. The calcite crystal prisms are diagonally layers on top of the aragonite tablets which are horizontally stacked like a brick wall.

Other animal shell examples include cockles which produce aragonite only shells and oysters which produce calcite only shells. Different animals grow slightly different forms of calcium carbonate and some forms are more vulnerable to changes in seawater pH.

As the seawater becomes more acidic there are less carbonate ions for animals to form their shells. The excess hydrogen ions in the seawater break up the calcium carbonate mineral into soluble calcium and carbonate ions, causing the shell to dissolve.

Experiment 3: Home-made ocean acidification!

Home experiment #3:

See video instructions and explanation of the experiment here.

Ocean acidification happens when carbon dioxide in the air is absorbed into the seawater in the oceans. Increasing carbon dioxide in the air can come from many sources, humans, cows, and other animals breathe out carbon dioxide. Cars and factories can also produce carbon dioxide. It is predicted that future carbon dioxide in the atmosphere will continue to rise and will reduce the pH of seawater from 8.0 to 7.7 by the year 2100 (See the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change website link). This final home experiment demonstrates how the carbon dioxide we breathe out can change the pH of water.

You can download a document with all of the experiments here: shells_on_acid_home_experiments-accessible.

For more information about the ‘Shells on acid’ resources please contact:

Dr Susan Fitzer

Tel: +44 (0) 1786 46 7904

Email: [email protected]

Jail Wynd, Stirling, FK8 1DE

+44 (0)1786 27 4000

BOX OFFICE OPENING:

Tolbooth Tues-Sat 10am-5pm